“When mothers cry it does not bode well for a (our) nation’s future” were the pained and perceptive words of Tain Sway, a young revolutionary woman from Karenni nation.

She made that observation during FORSEA Solo Concert for Myanmar Nway Oo Revolution, which was launched by the country’s youth activists after the country’s military regime responded to peaceful nationwide anti-coup protest with its characteristic brutality and violence.

Tain Sway, a young revolutionary woman from Karenni nation.

The young revolutionary woman, part of FORSEA’s democratic struggle series, was referring to the mothers of the revolutionaries whose sons and daughters were killed in the country’s unfolding armed revolution as they sought to raid police stations, the regime’s military outposts and arms depots across various regions including her native state of Karenni (pronounced Ka Rein Ni).

Tain Sway, Karenni National Defence Force Battalion One (against the genocidal coup regime).

Tain Sway is chief administrator of the Karenni National Defence Force Battalion Number One, one of the hundreds of armed resistance groups that have mushroomed across the country since the February coup last year. She was previously active in the student union at her university in Loikaw, the capital of her predominantly ethnic Karenni region.

Tain Sway talked of a Karenni mother who walked into her guerrilla base and, in effect, enlisted herself to be a revolutionary, before her tears dried over the death of her revolutionary son. “I will do anything to advance the revolution. My son gave up his life for it,” Tain Sway’s recalled the words of the visibly bereaved mother who is now the chief admin officer of her PDF battalion.

Some years ago I met leaders of the Mothers of Srebrenicia who admiringly sought accountability for the genocidal slaughters of their sons in Bosnia and Hazegovena during the violent break-up of former Yugoslavia. I have also heard of news reportage about the (dim) possibility of the mothers of Russian soldiers – killed in action in Putin’s ongoing war against Ukraine – emerging as a force to end the Russian war. Recently – on 14 April – the New York Times’s Amanda Taub, the author of The Times’s Interpreter newsletter discussed the enormous impact of the Russian war on Ukrainian mothers even against the backdrop of Europe’s continentwide support, morally, logistically, politically and financially.

The mothers of Myanmar’s revolutionaries – and young war refugees – aren’t that lucky insofar as support from neighbouring societies and governments.

In a year, Myanmar’s expanding civil war has resulted in a refugee population of estimated 800,000 – internally displaced persons or IDPs. The country’s immediate or distant Asian neighbours – such as Thailand, China, India or the Association of South East Asian Nations – are not welcoming of the war-displaced mothers from Myanmar.

Quite the opposite.

Whiling forcing the war-fleeing mothers of Myanmar back to the war zones inside the country, the Thai authorities have built barbed wire fences along the Myanmar-Thai borders. These borders have seen intense fighting between the coup regime troops and the combined revolutionary forces of Ethnic Resistance Organizations and People’s Defence Forces, including Tain Sway’s Karenni People’s Defence Force. The regime uses Russian- and Chinese-supplied combat helicopters and fighter-jets to bomb civilians and villages to break the morale of the resistance groups which draw their support from grassroots communities internally, in the total absence of any foreign support and solidarity.

Still, the resistance is expanding and holding out – against all odds.

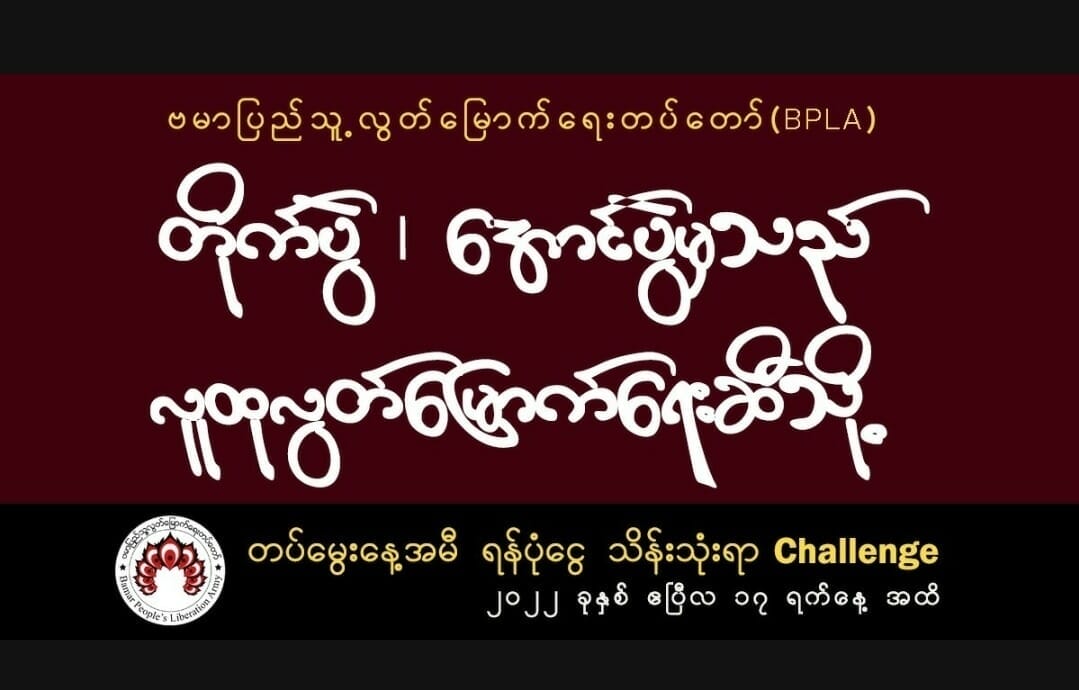

Karen National Liberation Army General Bawt Kyaw Hae (right) and Maung Saungkha, Founder & Commander of Bama People Liberation Army (BPLA) seen at the 1st anniversary of BPLA’s founding, Kawthulei or Karen State, Eastern Myanmar, 17 April 2022

To my ears, Tain Sway’s words – mothers of revolution crying and what it signifies for the future of Myanmar – continue to reverberate, especially the tale of one Karenni mother who wanted to join the revolution after she lost her son to the cause.

These crying mothers of Myanmar’s revolution are in fact the ones who should be looking forward to attending university commencement ceremonies of their sons and daughters in universities and colleges or feeling hopeful about the prospects of their children’s professional advancement, or a good harvest or small businesses, I thought to myself.

When the regime’s expected violent crack-down, which include summary executions, massacres, arbitrary arrests and torture in detention, began, Tain Sway and many of her peers from all walks of life numbering in the thousands decided to take up arms. Tain Sway’s generation of activists see the armed revolution as the only way to end the futile cycle of peaceful protests, accommodationist party politics, the coup, the protests and the crack-down.

New Generation Z Recruits: Photo Courtesy of the Bama People’s Liberation Force.

That is an unprecedented feature and development of the 2021 Nway Oo Revolution, which is very unlike Myanmar’s previous waves of anti-coup and anti-military dictatorship protesters – 1962, 1975, 1988, and 2007 – largely peaceful, but also inconsequential.

Mun Awng, the most acclaimed preforming artist of the revolution and former Burmese exile from Norway, chimed in. In his words of support for the new generation’s resort to revolutionary violence:

“Our older generation from the 1988 nationwide uprising did not succeed. In my youthful days as a musician and anti-military activist, I was a minority voice who opposed revolutionary violence as a means to achieve our goal of a federal democracy. But now I am almost 60, and I unequivocally support the armed revolution.”

The mothers of Generation Z – whom Tain Sway talked admiringly of – have become mothers of the revolution. They are also the peers of Mun Awng, and myself, who came of age in the decade before the fabled and failed 1988 uprising.

During the solo concert, both my guest performer Mun Awng and myself registered publicly our deepest appreciation and respect for Tain Sway and her generation to take care of the unfinished business of ending the murderous dictatorship – which has turned 60 on 2 March.

Myanmar’s young revolutionary networks such as Tain Sway’s are loosely interlinked with one another and operate under the umbrella terminology of People’s Defence Forces. The ranks of these PDFs swell when Gen Z from urban working class and rural farming backgrounds joined their more middle-class peers who left their university studies and professional lives to become fully-fledged armed revolutionaries. Most of them turned towards the nearest seasoned ethnic resistance organizations (EROs), which dotted virtually every region of the country. They looked for sanctuary, arms, training, battle supervision, and logistical support.

Groups like Tain Sway’s have become a newsworthy subject as some of the world’s leading news outlets such as The Guardian began reporting on them, typically with a mixed tone of unconcealed inspiration and painful realism.

Four of the most politically and militarily important among the EROs who are staunchly opposed to the coup have attracted and served as main patrons to thousands of anti-coup Generation Z activists such as Tain Sway.

Since the Russian invasion of Ukraine on 24 February – and the West’s unprecedented support – If not defence – for Ukraine’s resistance, the geopolitical equation has shifted, rather unfavourably, towards Generation Z-led Myanmar’s armed resistance against the genocidal coup regime in Naypyidaw. Very recently, China has signalled to any state actors – particularly the United States – that Beijing deems Myanmar as part of its sphere of (imperialist) influence.

It is not simply the cries of the mothers of Myanmar’s revolution that do not bode well for the country’s future but Beijing’s “unconditional support” for Myanmar’s murderous regime that has further stacked more odds against the anti-regime revolutionary movements.

It is not simply the cries of the mothers of Myanmar’s revolution that do not bode well for the country’s future but Beijing’s “unconditional support” for Myanmar’s murderous regime that has further stacked more odds against the anti-regime revolutionary movements.

The musician of resistance Mun Awng reminded the viewers, “the revolution must prevail, against all odds.” Tain Sway was seen nodding her head profusely when Mun Awng spelled out the pervasive sentiment – that “it is better to die fighting for the cause than living under the boot, again”.

Maung Zarni